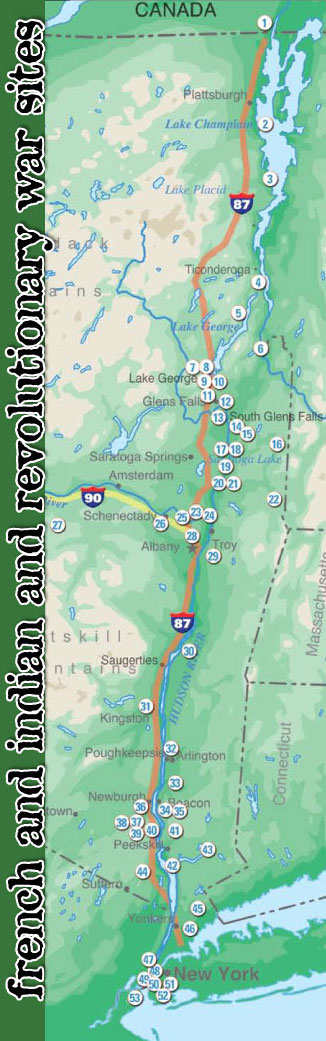

| |

COLONEL EPHRAIM WILLIAMS was born in Newton, Mass., February 24th,

1715. In early life a sailor; afterward a soldier, serving as a provincial captain in

Canada during the Anglo-French War, 1740-48. In 1750 the government granted him 200

acres of hand in the present townships of Adams and

Williamstown, Mass. He commanded all the border forts west of the Connecticut

River, and in 1755 was appointed colonel of a regiment to co-operate with Sir William

Johnson in a projected campaign against Canada. With a presentiment of his early

fall, he made his will at Albany, N. Y., devising his property for the support of a free

school, which became Williams College, at Williamstown, Mass. In 1854 the alumni

of this college erected a monument on the boulder marking the spot where he fell.

THE BLOODY MORNING SCOUT.– September 8th, 1755, was a day of three

desperate and bloody battles, fought within a few miles between Glens Falls and Lake

George – important engagements, even viewed from the present. This territory, known

as the "Great Carry," a land break in the waterways of the Hudson River. Lakes George

and Champlain, and the St. Lawrence, was

strategic territory and a bloody fighting

ground for ages, probably, between Indian

war parties: all though the seventy years'

struggle between England and France for

the possession of a continent and fought to

a conclusion within this region; and afterward. during the Revolution. No part of

America is richer in historic incident and interest than the region of this natural route

between the Hudson and the St. Lawrence.

Col. Williams' Grave, Near His Monument. |

The sanguinary defeat of Braddock's

expedition against Fort Duquesne in July.

1755, gave the French, through captured

papers, information that the English were

mustering men at Albany for an expedition

against Crown Point and Canada. and Baron

Dieskau, a brave and distinguished German

officer and field marshal of France, was

promptly sent to Crown Point with 3,000

men, quite one-third veteran regulars from French battle fields. Dieskau, exemplifying

his motto, "Boldness Wins," determined on the aggressive, and believing Fort Edward

(then Fort Lyman) feebly garrisoned, he moved with a flying corps of 600 Canadians,

. as many Indians and 300 regulars against this fort. September 7th he reached the

Hudson, below Glens Falls, and learned that Sir William Johnson had already reached

Lake George with a considerable force of raw provincials. General Johnson had with

him General Lyman, Colonels Williams and Titcomb (both killed on the 8th), Seth

Pomeroy, Ruggles, the afterward Revolutionary Generals Putnam and Stark, and

King Hendrick, the famous Mohawk sachem. Dieskau, with contempt for these

untrained and inexperienced farmers, decided to make a sudden attack upon them,

and early on the 8th marched toward Lake George.

In the meantime, Johnson's

scouts reporting Dieskau's force marching on Fort Edward, dispatched Colonel

Williams with 1,000 white men and 200 Mohawks under King Hendrick to the

relief of the threatened fort. Dieskau, learning this from a captured courier, instantly

prepared to ambush them by deploying his force in a semi-circle – his Canadians on one

side of the road, his Indians on the other and his regulars in the rear – all with knapsacks

off, lying flat and hidden in the underbrush, waiting the coming of Williams. Colonel

Williams, careless for an Indian fighter of experience, proceeding without scouts or advance

skirmishers, began to enter the "trap," when Dieskau's Mohawks of the St. Lawrence,

seeing their brothers of the Mohawk Valley in Johnson's advance, gave warning by firing

in the air, when the concealed Canadians and French poured from right and left into the

surprised provincials a terrific fire, which mingled with the war whoops of the savages,

filled the ravine with "a terror of sight and sound." King Hendrick was killed and the

Mohawks retired to cover. Colonel Williams led a charge up the hill on his right to turn

the enemy's flank and secure a more commanding position, mounted a boulder (on which

his monument now stands, about six miles from Glens Falls and three miles from Lake

George) to better see and encourage his men, and fell from a bullet in his head. (See

illustration – a reduced reproduction of Mr. Yohn's sketch, owned by the Glens

Falls Insurance Company.) Surprised, being shot down by an unseen foe, deserted by

the Mohawks, their commander dead, they retreated in confusion. lieutenant-Colonel

Whiting, now in command, partially rallied the fugitives, and with the aid of 300 men

sent out from Johnson's camp, checked

Dieskau's furious pursuit, and fighting from

behind trees, in frontier fashion, covered the

retreat to Johnson's camp at Lake George.

The English loss was 216 killed and 96

wounded, including a large number of

officers. The French also suffered considerable

loss. Few prisoners were taken, for the

scalping knife and tomahawk were freely

used, and the battle field at short intervals

was in possession of either side. This is a

brief summary of what has passed into fireside story, tradition and history, as "The

Bloody Morning Scout."

THE BATTLE OF LAKE GEORGE –

Dieskau, emboldened by his morning success,

fiercely attacked General Johnson,

and the battle raged all the afternoon with

and the battle raged all afternoon with. varying promise. Dieskau was severely

wounded and taken prisoner, Chevalier Montreuil succeeding in command of the French. General Johnson was also wounded, and

General Lyman, the lawyer and Yale tutor, commanded the English with great spirit

and bravery during the most of this hard fought battle. The French were finally defeated

and retreated in haste toward Ticonderoga.

BATTLE OF BLOODY POND.- Some 300 of the Canadians and Indians of the

French contingent went back to the field of "The Bloody Morning Scout," to scalp and

plunder the dead. While resting with their scalps and pillage on the margin of a stagnant forest pool (seven miles from Glen Falls and two from Lake George) they were

surprised by 200 men under Captain McGinnis, who had been sent from Fort Edward to

the aid of General Johnson. A sharp fight resulted in the utter rout of the French contingent. Captain McGinnis, commanding

the English, was mortally wounded. Tradition says that the bodies of upwards of 200 of the slain were thrown into this pool

for sepulcher, the water becoming so stained with blood as to give it the significant name

of " Bloody Pond," by which name it is still known to residents and tourists.

This is only a "boiled down" story of this sanguinary day of battles, memorable as

the first encounter of the hardy yeomanry of the New World with the disciplined troops

and experienced military commanders of the Old, and as the beginning of that confidence

which afterward led them to dare the great struggle of the Revolution.

Back to the Stories of the French & Indian and Revolutionary Wars. |