| |

FORT WILLIAM HENRY, at the head of Lake George, having been captured

and destroyed by the French under Montcalm the year before, Fort Edward

was the English outpost in 1758, with Fort Ticonderoga the nearest French

fortification.

The "Great Carry"– the few miles of land route between the Hudson and Lake

George, connecting the waterways between New York and Quebec – was strategic territory.

Small and larger expeditions and scouting parties were frequent (as they were all

through the years of the English and French War) to keep informed of the enemy's

strength, position and fortifications, to observe any tell-tale indications of his purpose

and to do him all the harm possible.

The most famous, persistent and daring officer on the English side was Robert

Rogers, notable as "Rogers the Ranger," who was constantly vigilant in harassing and

distracting the French, even to entering the very ditches of Ticonderoga and capturing

prisoners.

Rogers spoke French, was intelligent. alert, crafty, fearless, and was familiar with this

whole region of forest, mountains and waters. He and his rangers skated the frozen

waters and traversed the woods on snowshoes in winter, with light boats and canoes

skirted the shores, or on foot roamed the forests in summer, and from mountain tops and

other points of observation kept diligent watch of the French, and the French did the

same of the English.

Desperate conflicts therefore often resulted from these incursions, and one of them –

because of the numbers engaged, the hours of duration and severe loss – reached the

dignity of a battle and is the subject of this sketch.

In March, 1758, Israel Putnam returned to Fort Edward from an uneventful scouting, when Rogers was at once sent out with 180 men on an aggressive mission. After a

short march he camped the first night at Half Way Brook (Glens Falls), where Fort

Amherst was afterward built. He proceeded to Lake George and down its ice-covered

surface, his scouts in advance on skates. Hiding by day and marching by night, often

through the deep snow of the woods, with cold weather prevailing and obliged to avoid

fires, there were delays and much fatigue and suffering. Reaching the vicinity of the

mountain since known as Rogers' Rock, he proceeded into the woods west of this mountain,

sending a portion of his force on the frozen surface of Trout Brook, the remainder,

equipped with snowshoes, being held in reserve.

Unknown to Rogers, the French outlook from Rogers' Rock, or its vicinity, had discovered his coming, and reporting to Ticonderoga a force of French and Canadians with

200 Indians were sent to oppose him, and advanced up the same brook down which Rogers'

advance was moving.

At about 3 o'clock in the afternoon about 100 Indians were met by Rogers' advance

and were at once fired upon. Many Indians fell and the rest fled, pursued by Rogers'

men, with further loss to the Indians, until they were,confronted by the French soldiers.

The English fell back, firing as they went, to Rogers' position, with a loss of about fifty

men. Although greatly outnumbered, Rogers had no thought but to fight and fought

fiercely, maintaining a higher-ground position by retiring under pressure up the mountain

slope, firing from behind trees and resorting to woods methods, in which Rogers and his

men 'were experienced.

The French tried, and for a time vainly, to reach Rogers' rear, but, finally, about

two hundred of the enemy passed his flank, when he sent. Lieutenant Phillips with a few

men to prevent this threatening movement, It was too late, the men too few, and Phillips

was surrounded and forced to surrender.

Rogers, with his very few remaining men, some wounded and all fatigued from the

long struggle through the snow, made a resolute last stand as the sun was sinking in the

west.

This last stand is the subject of the painting by Mr. Ferris, owned by the

Glens Falls Insurance Company.

Rogers' remnant, at close quarters. really intermingled with the larger numbers of

the enemy, broke and fled, each on his own account. Phillips surrendered with promise

of protection, but every prisoner was cruelly massacred by the infuriated Indians, and the

wounded and exhausted met the same fate. To the delight of the French, Rogers was supposed to have been killed, as his overcoat and papers were found; but he escaped and

within a short time gave good evidence of the fact by taking French prisoners from under

the very guns of Fort St. Frederick at Crown Point.

Very few of Rogers' command escaped, and these suffered terribly from hunger

and cold, their great coats, blankets, baggage and supplies being lost and a cold snow

storm setting in.

The French loss was also large, and authorities consider the both sides loss as not

less than 300 – and yet this is but one of the many little known desperate conflicts which

counted for English supremacy in North America.

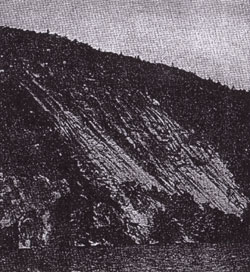

Rogers' Rock, Lake George, NY |

The wonderful escape of the pursued Rogers through the woods of that mountain

side is popularly accounted for this way:

Reaching the top of Rogers' Rock with its precipitous slant on its lake, or east side, he

reversed his snowshoes, and going back to a place where he could descend to the lake,

deceived the Indians. Seeing the two snowshoe tracks, both leading to the brink of the

precipice, they reasoned that two of Rogers' men were forced to slide down the awful

slope to the lake, and seeing a man (Rogers) running on the ice below, believed he had

been saved by spirits and that further chase was useless. Rogers does not give this account

in his published diary, or narrative.

"Rogers' Slide" is still pointed out to the tourist and excursionist, and the smooth

rock, bare from lake side to summit, shows to this day how his alleged slide cleaned the

steep slope of vegetation and earth.

This bold mountain of rock is however, worth pointing out and looking at, for behind

it and up its western side a sanguinary battle of some hours' duration was fought in 1758.

It is sometimes referred to as the "Battle on Snowshoes."

Back to the Stories of the French & Indian and Revolutionary Wars. |